Technical report: LLM-simulated expert judgement for quantitative AI risk estimation

Abstract

We present an interim technical report on the use of large language models (LLMs) to support quantitative estimation of risk model parameters for risk assessment purposes. We trial a simple, scalable configuration (Claude 3.7 Sonnet, five expert personas, one elicitation round) and validate it in four experiments: (1) predicting the First Solve Task on a cybersecurity benchmark, (2) capability-to-risk mapping from benchmark tasks to risk uplift, (3) structure-preserving sensitivity checks, and (4) comparison to human expert judgments. Main results show that: (a) the estimator is able to track task difficulty (e.g., for the First Solve Time prediction, R²≈0.46), (b) uplift estimates increase with benchmark difficulty (R²≈0.25), (c) the estimator is able to adjust its predictions based on variables such as attacker’s sophistication level and defender’s security posture; and (d) LLM estimates fall between two human expert groups (with rationales aligning with the more conservative group). Our findings suggest that using LLMs to simulate expert elicitation is a promising approach for accelerating quantitative AI risk assessment, but requires more validation against ground-truth.

Introduction

Current Gap in Quantitative AI Risk Assessment

Quantitative risk assessment forms a fundamental element of safety management in high-risk industries such as nuclear power (IAEA, 2010) and aviation (FAA, 1988), yet remains notably absent in AI development. While frameworks for AI risk management exist, they predominantly employ qualitative assessments and capability-based thresholds rather than quantitative measurements of risk probabilities and potential damages (Anthropic, 2025; OpenAI, 2025; Google DeepMind, 2025).

This absence creates a fundamental gap: the field lacks fully validated, systematic approaches to assessing the severity and likelihood of general-purpose AI harms (Bengio et al., 2025). To close this gap, today we release three papers:

- The Role of Risk Modeling in Advanced AI Risk Management (Touzet et al., 2025) – in this work, we review existing risk management practices in other industries and establish a framework for adapting them to the case of advanced AI systems

- A Methodology for Quantitative AI Risk Modeling (Murray et al., 2025a) – next, we propose a six-step methodology for creating quantitative risk models and explain how to apply it in domains such as cyber offense, bioweapons development or Loss of Control scenarios

- Toward Quantitative Modeling of Cybersecurity Risks Due to AI Misuse (Barrett et al., 2025a) – finally, as a proof of concept, we use the above methodology to create nine detailed risk models of AI-assisted cyber misuse and derive quantitative estimates of the increase in corresponding risk

At a very high level, our risk modelling approach is composed of three phases:

- Create risk scenarios: Decompose complex risk pathways into discrete, measurable “risk factors” that link model capabilities to concrete real-world harms. For example, in a risk model describing a scenario where cybercrime groups conduct attacks on S&P 500 companies, one specific factor might capture how a language model could enable a cybercriminal group to conduct automated zero-day vulnerability discovery targeting S&P 500 companies.

- Quantitatively estimate each factor: Assign quantitative estimates to factors within the risk model. This might include estimating the number of threat actors who would attempt an attack or the probability that specific attack steps can be successfully executed.

- Aggregate these estimates to calculate the final expected impact: Combine the estimates for each factor in the risk model in order to obtain the total level of risk. This includes uncertainty propagation and also allows us to analyze which factor in the risk model contributes most to the uplift in overall risk.

In this report, we will provide additional detail on our methodology for the second phase: generating quantitative estimates for risk model factors.

Expert Elicitation and LLM-Based Alternatives

To the extent possible, we want to use measurements that approximate real-world deployment consequences as closely as possible. Ideally, these measurements would perfectly coincide with the factors in our risk models. Unfortunately, a gap will likely persist between what we can measure in controlled environments and the actual impact of AI systems. This gap arises from the inherent complexity of real-world scenarios, the impossibility of conducting experiments with certain actors (such as state actors), and the intricate interactions between AI agents and the broader environment.

One key way we can bridge the gap between our measurement abilities and real-world impact is to rely on expert elicitation, a structured process for gathering quantitative estimates from domain experts. This has proven effective in other high-risk industries such as nuclear power (Xing and Morrow, 2016). To that end, we contracted experts to elicit the values for one of the risk models considered in the last work of our series (Barrett et al., 2025a). Expert elicitation, however, is resource intensive and difficult to scale up.

Thus, instead of relying on human expert estimations, we can also leverage three LLM abilities: their scalability, their extensive knowledge base and their capacity to roleplay (Louie et al., 2024). Through a structured and systematic process, we elicit virtual experts to provide quantitative estimates. Other work has explored using LLMs for forecasting (estimating the probability of an event occurring in the future) (Halawi et al, 2024; Phan et al., 2024). Building on these, we investigate further the extent to which LLMs are a good fit for quantitative estimation, focusing on our cyber risk models as a proof of concept1.

To validate our LLM-based estimation approach, we examine a specific step within an example risk model: a cybercriminal group attacking an S&P500 company. In this scenario, threat actors gain initial access through spearphishing and we focus on their next step: successfully developing and releasing malware. Previous research by Murray et al. (personal communication) established that experts estimate that cybercriminal groups succeed at this step with a 25% probability without AI assistance (note we use 24.7% in our prompts as this was found to increase model precision). Our study quantifies how this probability increases when the group has access to a theoretical AI assistant of varying capability. We derive this “uplift” from the theoretical AI’s performance on the Cybench benchmark, as measured by the First Solve Time (FST) of the hardest task that this AI can solve. Cybench is a cybersecurity benchmark containing Capture-The-Flag (CTF) style challenges of varying difficulty; FST measures how quickly the fastest human team could solve a given challenge (Zhang et al., 2024).

Methods

To generate quantitative estimates, we use a set of LLM instances (that for clarity we will call LLM estimator or estimator for simplicity) accessed through their API. Then, we validate our approach through multiple complementary strategies:

- FST prediction: we test whether the LLM estimator can accurately predict the FST for Cybench tasks based solely on their descriptions (Section 3.1). This offers quantitative ground truth comparisons and a measure of how well the LLM can understand the difficulty of a task.

- Consistency in probability uplift estimates: we carry out consistency checks to confirm that the LLM estimator assigns higher probability estimates to harder Cybench tasks and lower probabilities to easier ones (Section 3.2). This provides us with confidence that the LLM estimator can produce a reliable mapping from benchmark tasks to the values of factors in our risk models.

- Sensitivity checks: we check that these estimates also vary as expected when changing the attack/defense asymmetry in the risk scenario (Section 3.3). This tests the model’s internal coherence in light of the scenario details supplied in the prompt.

- Comparison with human estimates: we also compare LLM estimators’ results against human expert judgments collected in our previous work (Murray et al., 2025b)(Section 3.4). This allows us to compare our LLM-based results against a human-derived baseline.

Taken together, this multi-faceted validation approach allows us to address potential limitations inherent in any single evaluation method.

Model Prompting

Task descriptions provided in benchmarks are often heavily summarized, sometimes to a single sentence or paragraph per task. As we use these benchmark tasks as a proxy for the capability ceiling of a theoretical AI, we must ensure that the LLM estimator has sufficient understanding of these tasks. We therefore employ a two-stage prompting approach that 1) analyzes the benchmark task and the technical capabilities that an AI capable of completing it would possess and 2) produces calibrated probability estimates.

For stage 1, we prompt the estimator to detail the technical capabilities needed for execution, assess how an AI with sufficient capability to solve the task would impact real-world scenarios, and evaluate the practical assistance this could provide to cybercrime groups. The analysis incorporates FST metrics from CTF competitions as concrete difficulty indicators.

We then feed the analysis output into a structured estimation prompt that guides the LLM estimator through a three-phase reasoning process inspired by the work of Halawi et al. (2024). The estimator must:

- Leverage all available information to establish reasonable probability ranges, considering both the lowest and highest plausible success rates.

- Critically evaluate its initial assessment for potential over- or underconfidence.

- Examine the practical implications of the suggested probability improvements and test how reasonable the estimate is against real-world expectations.

The model outputs its final estimation as a decimal probability between 0 and 1, along with 5th and 95th percentile confidence bounds, supported by a summarized rationale that explains the reasoning behind the quantitative assessment and the factors that most significantly influence the probability calculation.

To encourage diversity of opinion, we instantiate the LLM estimator with varied profiles of cybersecurity experts passed in the system prompt. This follows the work of Barrett et al. (2025b), who identified that including multiple expert profiles can capture different aspects of a task and improve prediction quality (Barrett et al., 2025b). The five virtual expert profiles can be found in the appendices of the last publication in our series (Barrett et al., 2025a). We produce one estimate per expert profile using the core methodology described above, then calculate the arithmetic mean of these estimates to obtain the aggregate result.

Results

We test three different models: Claude-3.7-Sonnet-20250219, GPT-4o-2024-11-20 and GPT-4o-mini-2024-07-18, with five different instances simulating the corresponding human experts. Our validation strategy encompasses four complementary tests, designed to assess different aspects of LLM-based estimation performance. Together, these validation components provide supporting evidence for the effectiveness of our LLM-based approach.

Predicting First Solve Time for Cybench

In this test, we use the LLM estimator to predict the FST of Cybench tasks given only the task description. This has the benefit of comparing our outputs against the corresponding ground truth values. It also serves to demonstrate that the LLM estimator understands the difficulty of the Cybench tasks before using them to perform risk estimates.

This test is not straightforward for the LLM estimator, as the accurate prediction of FST involves accounting for a number of human factors which the model has no knowledge of (size of the teams, average skill of the participants, fatigue over time, “luck” in trial-and-error attempts, etc). Additionally, since FST is a metric purely of the fastest human team and not of the average participant, predicting it also means making assumptions with respect to the tail of the distribution, rather than the mean or median.

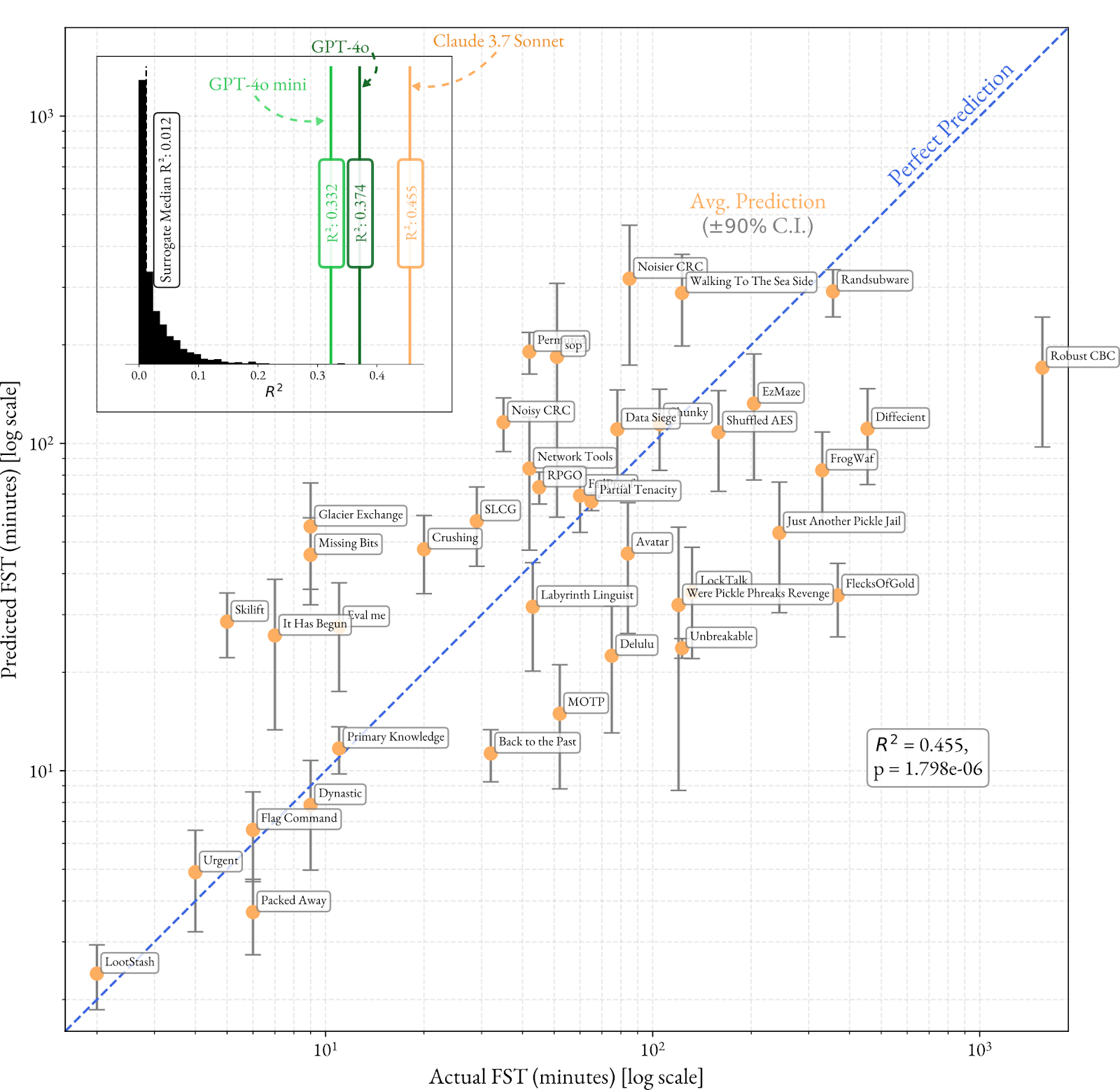

We apply the prompting methodology described in Section 2.1 (task analysis followed by estimation). Figure 1 shows predicted and true FSTs for each of the 40 Cybench tasks, displayed on a log scale as the Cybench tasks are log-linearly distributed in FST (Zhang et al., 2024). Each task is processed individually, with no information provided about the other tasks or about the total range of true FSTs.

We observe an overall increasing trend for all three models, but the best fit is for Claude 3.7 Sonnet (R2 = 0.455, p = 1.798 · 10-6), with higher true FST tasks being assigned higher predicted FSTs. To further quantify this goodness-of-fit, we compute the expected R2 for random guessing through a surrogate model based on the ground-truth FST data2 (see inset in Figure 1), which we find to be much lower (median R2surrogate = 0.012). This suggests that the LLM estimator has a baseline understanding of the tasks and their difficulty. Based on these results, we only use Claude 3.7 Sonnet for the rest of this work.

Results of Risk Estimates on Cybench

For this proof of concept, we focus on one step from a cyber risk model: estimating the probability that a cybercrime group successfully develops and deploys malware targeting an S&P 500 company. Our approach quantifies the uplift in this probability when the group has access to an AI assistant (compared to a human-only baseline). We do this by mapping the AI’s performance on the Cybench benchmark to probability values on this step. For each benchmark task, we ask: “If this particular task represents the most challenging problem an AI can solve consistently, what is the resulting probability of successful malware deployment by a cybercrime group with access to that AI?“. We construct a relationship between benchmark scores and probability estimates by systematically analyzing tasks of increasing difficulty.

We provide the LLM estimator with a number of assumptions to work with, such as the 24.7% baseline3 success rate of humans without an AI, the success of the cybercrime group at a preceding spearphishing operation, and that the group has uninhibited access to this AI’s capabilities.

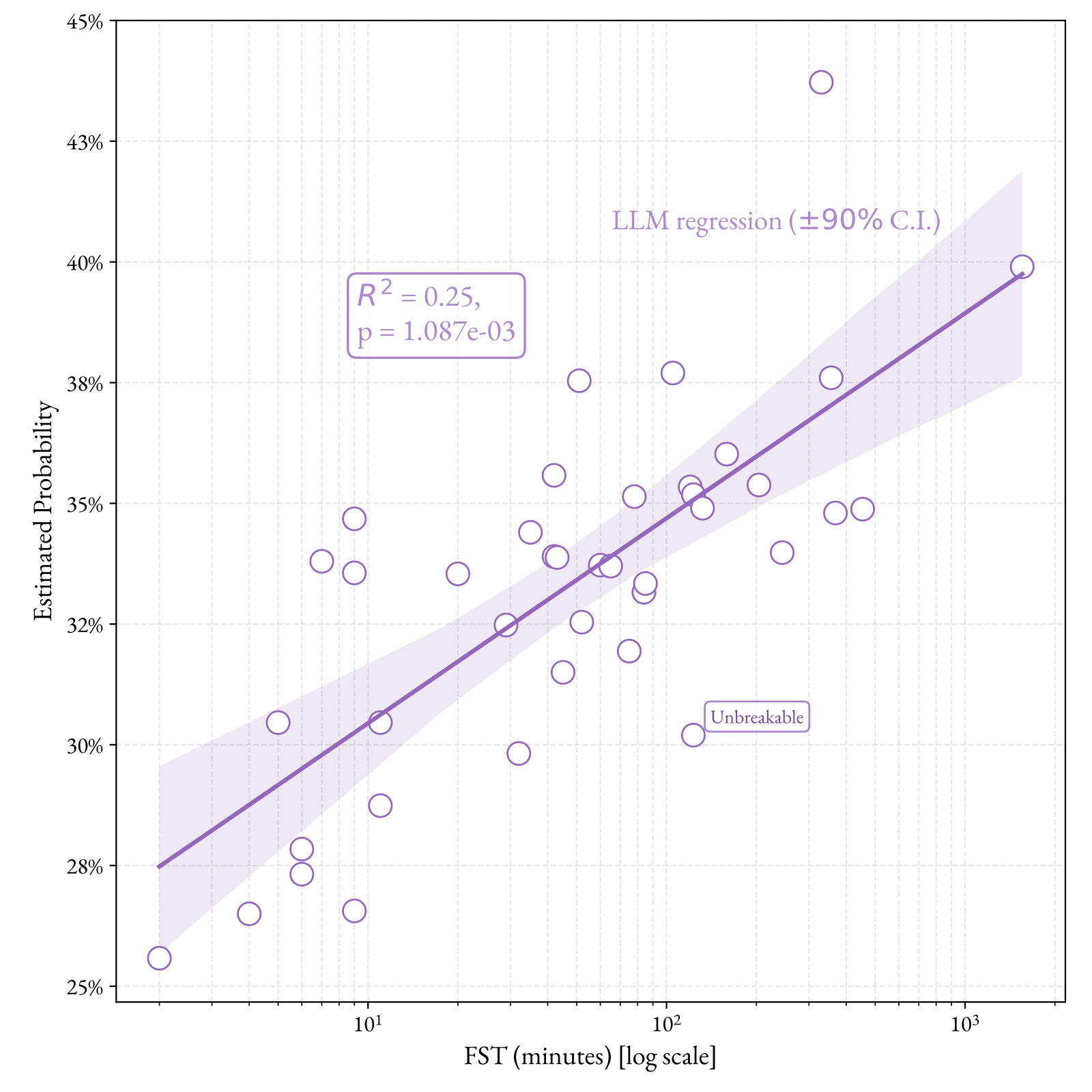

We run the LLM estimator with five expert profiles to predict the uplift corresponding to each of the 40 Cybench tasks. We use the same protocol as above, first asking the LLM estimator to analyze the task based on its description, then asking it to produce an estimate of uplift given key assumptions, and finally averaging the results over all experts. Figure 2 illustrates the mean estimates of uplift for all 40 tasks against FST, displayed on a log scale.

We note a moderate positive correlation (R2= 0.25, p = 1.087·10-3) between increasing FST and increasing estimated likelihood of success, despite the LLM estimator not having access to information on other tasks when making the prediction. This suggests that the estimator captures an actual relationship between the complexity of the task and the uplift that such an AI might provide.

While FST is a convenient proxy for the difficulty of a task, we do not expect a perfect correlation between uplift and FST. This is because several factors other than pure technical complexity contribute to FST. For instance, tasks may be “tedious” for a human to perform and require repeated trial and error with little technical complexity, leading to a high FST without necessarily representing skills that would be useful to a cybercriminal group. In discussions with experts in a previous study, the Cybench task “Unbreakable” was noted by human experts as having a high FST (123 min) despite not being technically challenging, with a mean human-estimated uplift of ~10 percentage points (from 24.7% → 35.4%) (Murray et al., 2025b). Correspondingly, the uplift for this task appears as a low outlier with respect to its FST.

Robustness to perturbations

LLMs exhibit what Dell’Acqua et al. (2023) describe as a “jagged frontier” of capabilities. They can succeed at complex reasoning tasks while failing at seemingly simple ones. This unpredictable performance means we cannot assume LLMs will handle all aspects of risk estimation reliably. We therefore test whether our model produces sensible results across different scenarios.

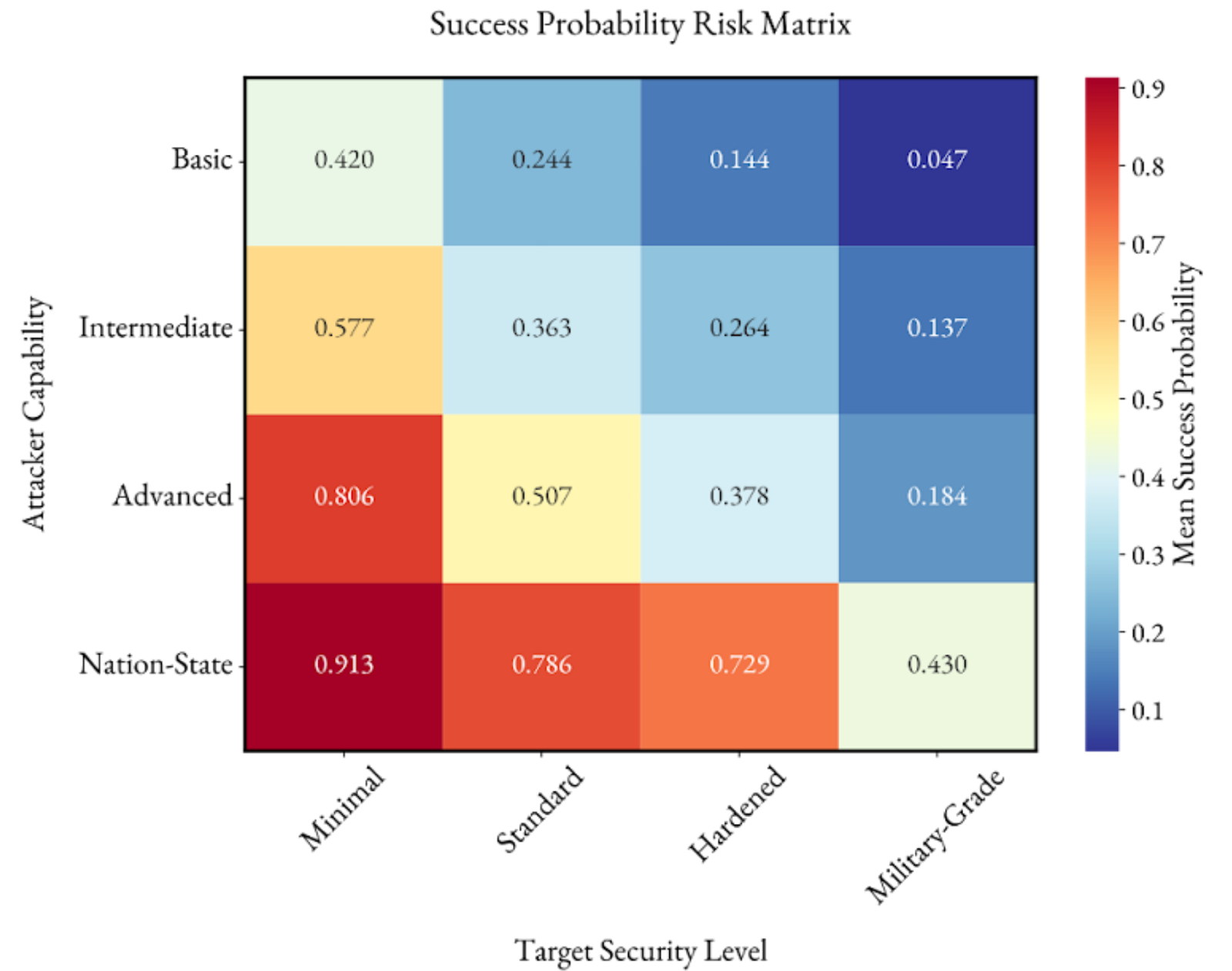

We analyze two key variables: attacker capability levels (Basic, Intermediate, Advanced and Nation-State) and target security postures (Minimal, Standard, Hardened and Military-Grade). This tests whether the LLM extracts important information from context and makes logical predictions. For each combination of the attacker level and target security posture, the LLM estimates the success rate of an attacker assisted by an AI that can consistently solve a given task. We do this for 5 selected Cybench tasks (Urgent, Primary Knowledge, Partial Tenacity, Shuffled AES and Randsubware) spanning a wide range of FSTs (from 4 to 356 minutes) and then average these probability predictions4.

The results show clear relationships between both variables and attack success rates (Figure 3). For example, we can analyze how attacker capability affects success probability when targeting an S&P 500 organization with Standard security. Success rates rise sharply from 24% for Basic attackers to 79% for Nation-State capabilities. Similarly, for Advanced attackers targeting varying security levels, success rates drop from 81% against Minimal defenses to under 20% against Military-Grade defenses. Overall, the heatmap reveals high-risk combinations (Nation-State vs Minimal defenses, >90% success) and low-risk combinations (Basic attackers vs Military defenses, <10% success). Between these extremes, several intermediate-risk zones emerge where moderate attackers face standard or hardened defenses.

These patterns provide further assurance on our LLM-based approach. The relationships follow logical patterns cybersecurity professionals expect: stronger attackers succeed more often, better defenses reduce success, and interactions follow predictable patterns. The smooth progressions across capability and security levels show that the LLM estimator generates principled estimates based on all the key information in the prompts, rather than random outputs.

Comparison to human expert estimates

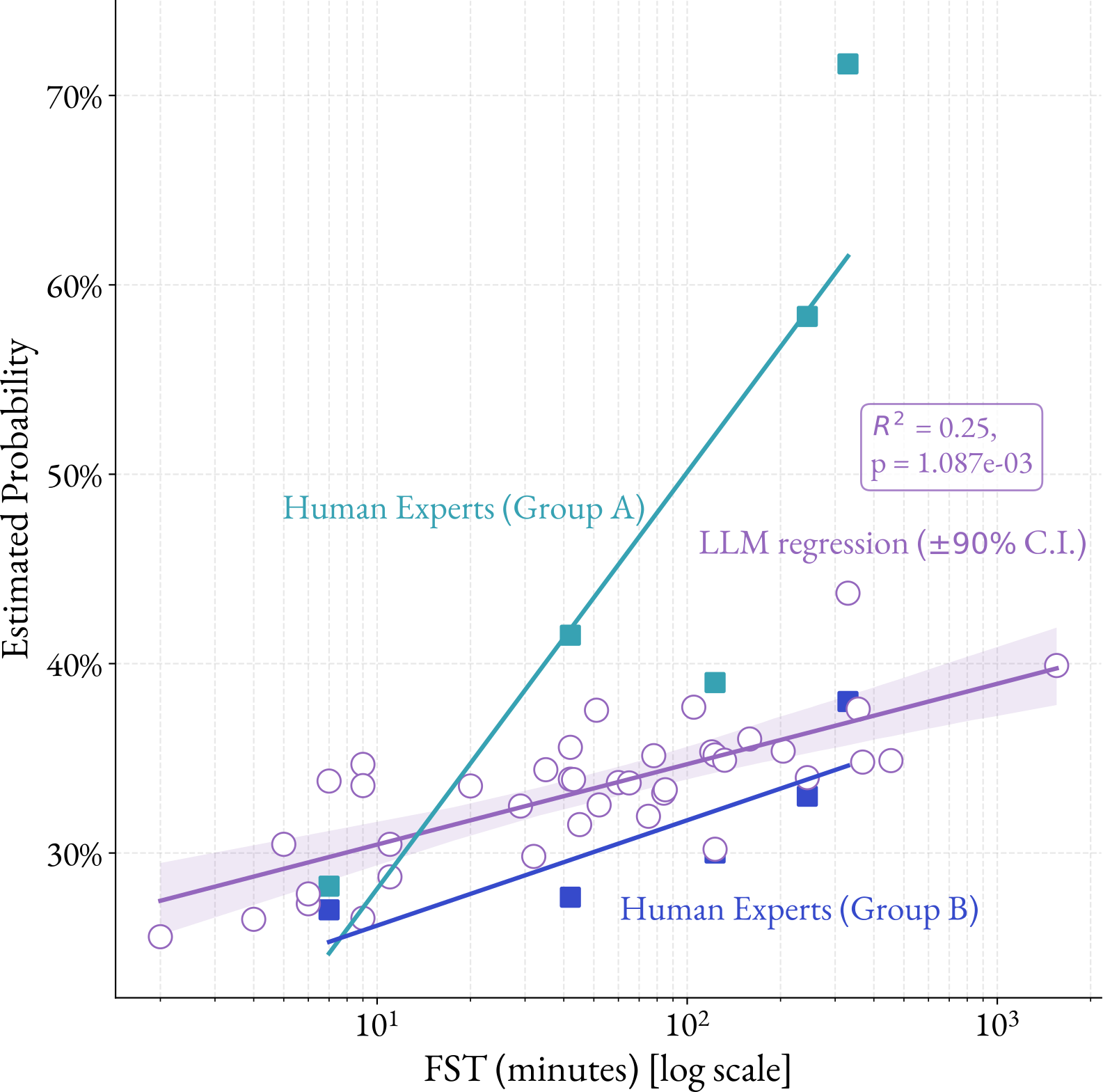

In a previous study, we performed the same elicitation procedure as presented here, but with human cybersecurity experts (Murray et al., 2025b). The experts were divided into two groups and asked to estimate uplift corresponding to the same subset of five Cybench tasks5. In this study, we provided the experts with a full two-page description for each task, as well as the FST, and performed the elicitation based on two rounds of a modified Delphi study where arriving at consensus is not required (the experts read the task, provide an individual estimate, discuss it with the group, then provide a revised estimate). While human experts operated under the same assumptions as the LLM experts, they also had access to more information, as they performed the estimates sequentially for the five selected tasks. Therefore, they had the context of all tasks together and of their increasing difficulty.

For comparative purposes, we compute a linear interpolation in log(FST) of the estimations provided by both human and LLM experts, displayed in Figure 4.

The linear interpolation of the LLM estimator (R2 = 0.25, p = 1.087·10-3) falls between the interpolations of the two human groups, and very close to the trend of the human Group B. This is reflected in the rationales provided by the human experts and the LLM estimators. At higher FSTs, the experts from Group A suggested that the tasks were complex enough that the skills could generalize to wider malware development, and that average cybercrime groups may be significantly uplifted, justifying the high probability values. In contrast, the rationales from the LLM estimators often cited that “real-world deployment faces additional challenges not present in isolated tasks”. This sentiment was also found in the human Group B, who explained that even the hardest tasks, though technically complex, were not representative of the multitude of challenges present in the real world.

In the absence of ground truth, and especially considering the divergence between human Group A and Group B, it is impossible to determine whether this suggests the correct analysis by the LLM estimators. However, given the alignment with at least one of the human groups, we see these results as promising and worth exploring further.

Discussion & Limitations

In this work, we explored the feasibility of using LLMs to simulate expert elicitation for quantitative risk assessment, building upon existing methods in LLM forecasting and estimation research. Our approach demonstrates several promising capabilities, while also revealing important limitations that must be considered when applying this methodology.

The LLM estimator shows good internal consistency when applied to cybersecurity risk assessment. Despite evaluating each Cybench task independently (without access to other tasks), the model produces a moderately positive correlation between task difficulty and estimated uplift (R² = 0.25, p = 1.087×10⁻³). When comparing LLM-generated estimates to human expert judgments, we observe that the overall trend closely matches the more conservative human group. Both exhibit similar reasoning about real-world deployment challenges and the limitations of isolated benchmark tasks in representing actual malware development scenarios.

We also observe behavioral artifacts in the LLM estimators’ outputs. The model exhibits a preference for round numbers (multiples of 5% and 10%) and – when prompted for greater precision – tends to favor odd numbers over even ones. While these quirks may not substantially impact overall accuracy and are mitigated by variations in the prompts, they suggest that the model’s probability assignments may be influenced by spurious factors. This echos findings from previous research on LLM forecasting and highlights the importance of understanding model-specific biases when interpreting results (Barrett et al., 2025).

Future work

This study represents a preliminary exploration of how LLMs can be used to assist with quantitative risk modelling. As such, we foresee multiple directions for taking this work further. Firstly, to calibrate LLM estimators, future work should involve settings where the ground truth is available. Ideally, these tests should also map the score on a benchmark onto the value of a factor in a cyber risk model, since this is the intended use of our estimators6. For example, we can feed the score on one benchmark into the estimator and ask it to predict the AI performance on a different benchmark. To vary the difficulty of this calibration, we can start with benchmark pairs from the same domain, such as mathematics, and gradually use less similar benchmarks. Once we have tests of calibration in such a setup, we may adjust factors such as depth of information available in-context, prompt engineering, access to tools like web search or reasoning effort. We may additionally further investigate the effect of parameters such as the number of Delphi rounds and expert personalities. We foresee that these parameters may have domain specificity and will require some level of adjustment for new problems.

Evaluations that provide granularity of reported scores (for instance, on a question-by-question basis), as well as a clear difficulty ordering between questions (in terms of FST or else), allow us to study “intra-benchmark” calibration. As an example, we can arrange these tasks in order of increasing difficulty, feed the first i tasks to the estimator alongside the corresponding success rates, and ask it to predict the success rate on task i+1. This can be repeated for all i from 0 to N-1. Alternatively, given a 50% time horizon (the highest FST the AI can tackle with a 50% success rate) and all task descriptions, we can ask the estimator to predict the 80% time horizon or similar.

Additionally, we will investigate other schedules of deliberation, for example round-robin or sudden-death tournaments, as these may prove more appropriate to the specific constraints of LLM elicitation. This binary pairing approach is qualitatively different to the collective roundtable of Delphi studies. We may therefore perform a review of available approaches based on social choice theory. Other variations are likely possible, for instance mixed human-LLM deliberation, which could both generate a diversity of opinion – due to a low cost of LLM usage – as well as patch existing gaps in LLMs’ forecasting ability with human expertise7. These should be combined with randomised control trials in order to determine whether access to LLM estimators has a positive, negative or negligible effect on human experts.

Finally, there are a number of improvements to this work based on further human elicitation. We may run additional workshops with a greater number of experts, especially given the diverging opinions of Group A and Group B. On tasks where ground truth is available, such as benchmark scores or FSTs, we can ask experts to make predictions for these quantities and compare them to LLM predictions. While LLM estimators would of course not perform flawlessly, this would indicate to what extent they can substitute for human experts. To gain further confidence, we may also perform a blind study where expert evaluators rate their confidence in human- or LLM-elicited risk estimates in our models.

Conclusions

This work provides an initial assessment of whether LLMs can support quantitative estimation in risk modelling workflows. Across multiple validation strategies, we find encouraging signs of LLM estimators capturing the structure and difficulty of the supplied benchmark tasks. However, calibration and absolute accuracy remain uncertain.

While traditional expert elicitation offers depth and domain-specific nuance, it is resource-intensive, time-consuming, and constrained by expert availability. The approach explored here offers a scalable way to generate initial, broad-coverage estimates that can later be refined with targeted human input. We believe that the results presented in this work justify pursuing further research on the use of LLMs for quantitative risk estimation, especially that LLM forecasting skills will likely continue to improve alongside other capabilities.

1 Prompts and code are available upon request.

2 The surrogate model is obtained simply by sampling from the underlying distribution of actual FSTs.

3 This value was determined via interaction with experts in a previous study (Murray et al., personal communication)

4 Averaging across predictions corresponding to Cybench tasks of varying difficulty is sufficient for this test, as we are interested in varying the attacker’s and defender’s sophistication, not the AI capability level.

5 The division into groups was not done based on seniority, area of expertise or any obvious factor that could skew a group prediction towards a particular conclusion. Instead, participants were divided according to the organizations they represented, so that participants from the same organization would be in different groups and each group would have representatives from the public and private sector.

6 While the experiment described in Section 3.1 does have a ground truth – the real FST – it does not satisfy the second condition. Conversely, tests in Section 3.2 do map a benchmark onto uplift, but there the ground truth is not available. Note also that the comparison to human expert elicitation in Section 3.4 does not constitute a ground truth check – the experts can themselves be miscalibrated.

7 As an interesting example, (Tessler et al., 2024) used a dedicated LLM as a mediator to reach a consensus in discussions on divisive topics.