Narrowing the gap between AI benchmarks and real-life cyber risk assessment

When Anthropic disclosed earlier this year that it had disrupted an AI-orchestrated cyber espionage campaign, the announcement confirmed what security researchers had been anticipating: advanced AI systems are now actively enhancing real-world cyberattacks. Yet knowing that models can write convincing phishing emails or identify software vulnerabilities doesn’t tell us how much additional harm actually results when those capabilities reach malicious actors. Current risk frameworks focus on capability thresholds, which do matter, but capabilities are sources of risk rather than risk itself. The distance from “this model can do X” to “X causes Y dollars of damage” involves many intervening factors that existing evaluations don’t capture.

Over the past year, SaferAI has developed a methodology to bridge this gap, drawing on risk management practices from nuclear power, aviation, finance, and other safety-critical industries. We’ve released a technical report that applies this methodology to AI-enabled cyber offense. We built nine detailed probabilistic risk models covering scenarios from amateur phishing to nation-state espionage. The findings suggest that current AI systems already provide meaningful uplift to attackers across most scenarios we examined, with the effect coming not from any single factor but from compounding gains in attack volume, success rates, and potential target reach. This post summarises our approach and what we learned.

The problem

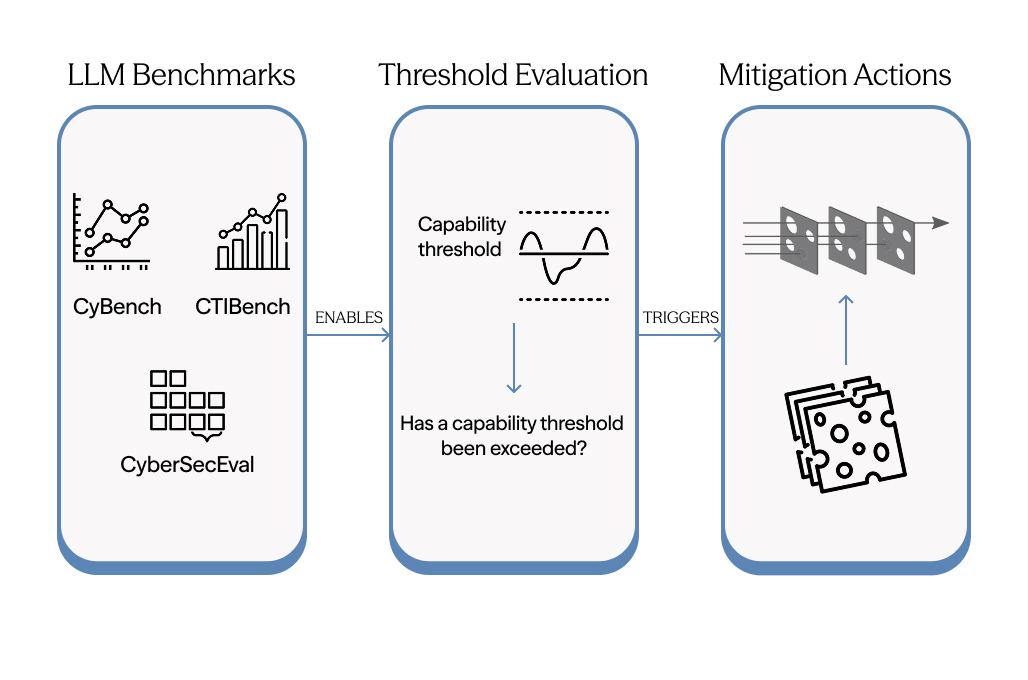

The standard approach to frontier AI risk management follows a straightforward logic: evaluate models against capability benchmarks, and if they exceed certain thresholds, trigger corresponding mitigations. This framework has shaped how the industry thinks about safety, and it reflects genuine effort to create structured, repeatable processes. But as AI systems get better, its limits become clearer.

The core issue is that capability evaluations measure hazards rather than harms. A benchmark might tell us that a model can generate functional exploit code or craft persuasive social engineering messages. What it doesn’t tell us is how often that capability translates into successful attacks, against which targets, by which actors, and with what consequences. These contextual factors determine actual risk, and they vary enormously across scenarios. An exploit-writing capability that poses serious concern in the hands of a organised cybercrime syndicate may be largely irrelevant to a hobbyist hacker who lacks the infrastructure to deploy it.

There’s also a temporal problem. Capability-based frameworks are fundamentally reactive. They wait for models to demonstrate concerning abilities, then respond with mitigations. This makes sense when capabilities emerge gradually and predictably. It becomes more problematic as AI development accelerates and capabilities combine in unexpected ways. By the time a benchmark flags a concern, the capability may already be deployed across multiple systems and accessible through various channels.

Benchmarks themselves are imperfect proxies – they measure performance on specific tasks under controlled conditions. Real-world risk depends on how capabilities generalise, how actors adapt them to their purposes, and how they interact with existing tools and techniques. A model that scores modestly on a capture-the-flag security benchmark might still provide substantial assistance to an attacker who knows how to prompt it effectively and integrate its outputs into a broader workflow.

None of this means capability evaluations are without value. They provide important signals and have driven meaningful safety investments. The question is whether they’re sufficient on their own, or whether they need to be embedded within a broader framework that connects capabilities to real-world outcomes.

Our approach

Our work on this problem has unfolded across three interconnected papers.

We began by examining how other safety-critical industries manage risk. Nuclear power, aviation, finance, cybersecurity, and submarine operations all face the challenge of anticipating rare but consequential failures in complex systems. Despite their differences, these industries share a common insight: no single method is sufficient. All employ hybrid approaches that combine probabilistic risk modeling (using statistical methods to estimate likelihoods and consequences of different failure scenarios) with deterministic safety baselines (hard limits and design requirements that must be met regardless of probability calculations). They build detailed scenarios, quantify uncertainty explicitly, and update their models as new evidence emerges.

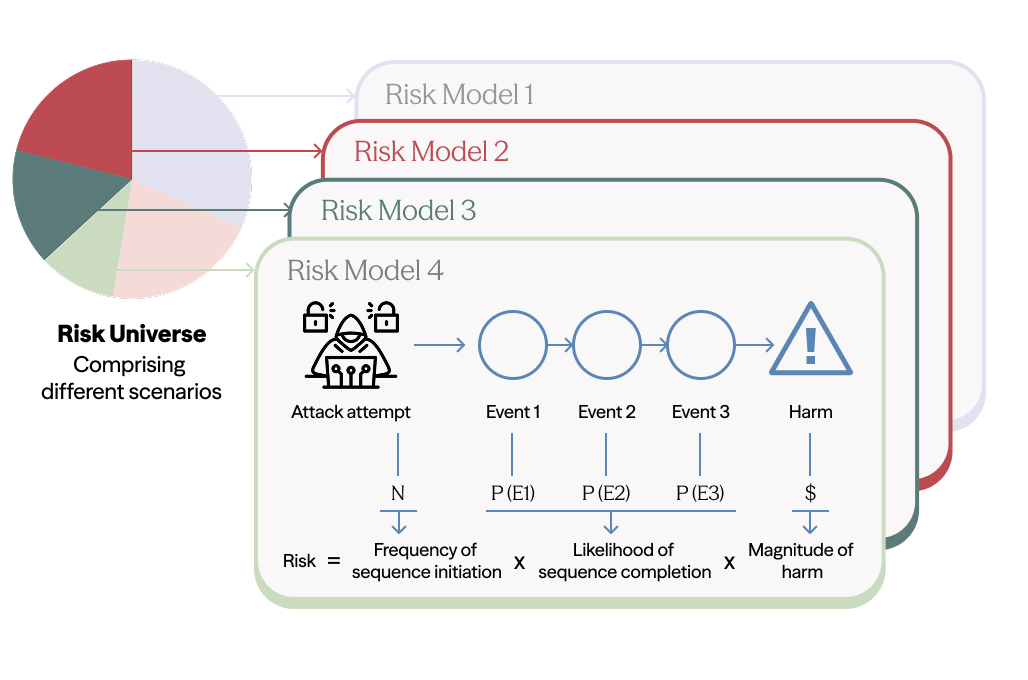

Drawing on those lessons, we developed a methodology for quantitative AI risk modeling. The core idea is to decompose risks into discrete scenarios, then estimate three components for each: the frequency of initiating events, the probability of the event sequence completing, and the magnitude of resulting harm. Where historical data is scarce, we use structured expert elicitation through modified Delphi protocols – a systematic method where experts provide independent estimates, review anonymized responses from their peers, and then refine their judgments through multiple rounds until reaching informed consensus. All estimates are represented as probability distributions rather than point values, making uncertainty visible.

The technical report we’re releasing applies this methodology to AI-enabled cyber offense. It serves as both a proof of concept and a source of initial findings about where AI is amplifying attacker capabilities.

What we did

We started by mapping the landscape of potential AI-enabled cyberattacks. This meant considering the full range of threat actors, from amateur hackers through to nation-state cyber units, alongside possible targets like financial services, healthcare, and critical infrastructure, and attack vectors including phishing, ransomware, denial-of-service, and data exfiltration. The complete matrix of combinations would be overwhelming, so we filtered down to nine representative scenarios using three criteria: historical prevalence, plausibility, and the extent to which AI capabilities might meaningfully shift the balance in favor of cyberattackers. The resulting set covers attacks ranging from low-sophistication business email compromise to state-sponsored espionage using polymorphic malware.

For each scenario, we built a detailed probabilistic model. We decomposed attacks into their constituent steps using the MITRE ATT&CK framework, which provides a standardised taxonomy of adversary tactics from initial reconnaissance through to final impact. We then established baseline risk estimates for a world without meaningful AI assistance, drawing on threat intelligence reports, incident data, and expert review. To estimate how AI changes these parameters, we mapped model performance on two cybersecurity benchmarks, CyBench and BountyBench, to real-world risk factors. We did this through a combination of a modified Delphi study with cybersecurity experts (for one scenario) and LLM-based estimation (for the remaining scenarios), which we validated against the human expert baseline.

The final step was propagating these estimates through Bayesian networks and running Monte Carlo simulations to generate overall risk figures. This approach lets us compare current state-of-the-art AI capabilities against both a no-AI baseline and a hypothetical “saturated” case where AI systems can complete all benchmark tasks. It also surfaces which components of the attack chain see the most significant uplift and where uncertainty in our estimates is highest.

Key findings

Across eight of our nine scenarios, current state-of-the-art AI systems provide measurable uplift relative to the no-AI baseline. The largest effect appears in lower-sophistication attacks like phishing and business email compromise, where AI assists with crafting personalised messages and processing information about targets at scale. At the other end of the spectrum, the models suggest more modest uplift for nation-state espionage operations, where attackers already possess substantial capabilities and AI tools may sometimes introduce operational friction rather than efficiency gains.

The uplift doesn’t come from any single source. All four main risk factors we modeled contribute: the number of actors attempting attacks, the frequency of attempts per actor, the probability of success at each stage, and the damage resulting from successful attacks. AI appears to help with both quantity and quality. It lowers barriers to entry for less sophisticated actors while also improving success rates for those who already know what they’re doing. When we examined individual attack stages, five MITRE ATT&CK tactics showed consistently higher AI-related uplift: Execution, Impact, Initial Access, Lateral Movement, and Privilege Escalation. But the pattern varied across scenarios, and some tactics that saw strong uplift in one model showed negligible or even negative effects in others.

One consistent finding was that uncertainty grows at higher capability levels. Experts were naturally less confident about what fully saturated AI capabilities would enable compared to current systems. This showed up clearly in wider confidence intervals for estimates tied to harder benchmark tasks. We also found that LLM-based estimators, which we used to scale the elicitation process, tracked human expert judgments reasonably well on probability estimates but tended to be more conservative when estimating quantities like number of actors or potential damage. This suggests LLM-assisted elicitation may be viable for expanding the methodology, though further validation is needed.

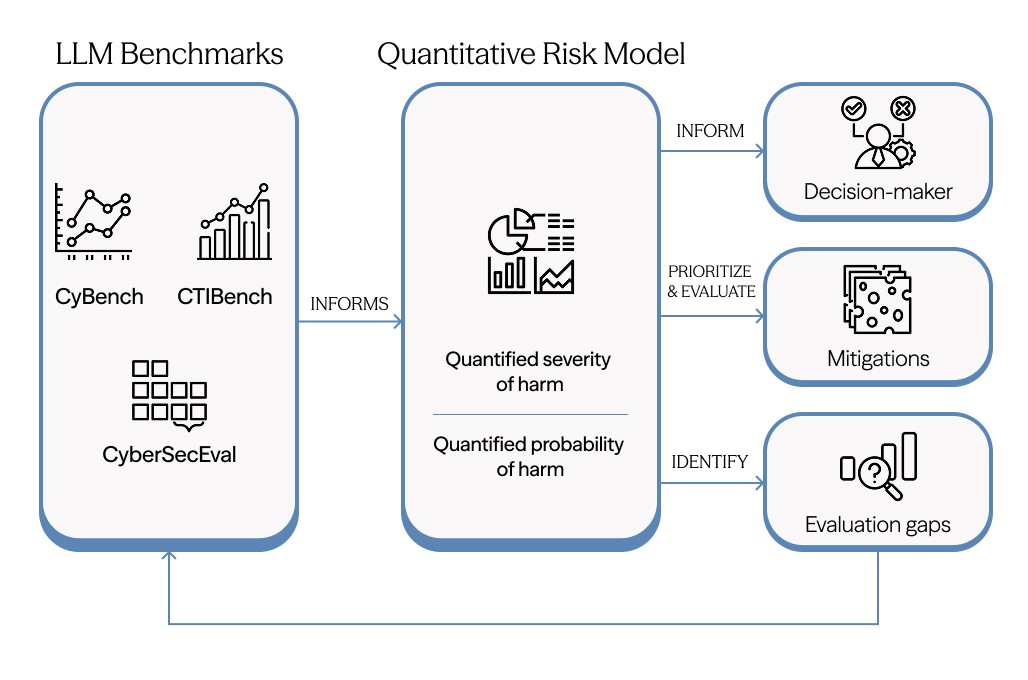

What this enables

For AI developers, this methodology offers a way to connect model performance to downstream consequences. Instead of asking whether a system passes a benchmark threshold, developers can ask how deployment would shift expected harm across realistic scenarios. This kind of analysis can inform not just go/no-go decisions but also more granular choices about access controls, rate limits, and monitoring. When you can see which attack stages benefit most from AI assistance, you can target mitigations more precisely.

Cybersecurity teams face a related challenge from the other direction. They know AI is changing the threat landscape, but translating that awareness into defensive priorities is difficult. The MITRE-level analysis in our models offers one path forward. If Execution, Initial Access, and Lateral Movement are seeing consistent uplift, that suggests where detection capabilities may need reinforcement and where automation on the defensive side could provide the highest returns.

For policymakers, the framework makes it possible to work backward from harm tolerances to capability limits. If a jurisdiction decides that a certain level of AI-enabled ransomware risk is unacceptable, the models can help identify what benchmark performance would correspond to that threshold and what mitigations would be required to stay below it. And for the evaluation community, this work highlights where current benchmarks fall short. Social engineering and operational technology security both lack robust capability indicators, leaving blind spots in risk assessment that new evaluations could address.

Limitations and what comes next

We want to be direct about what this work doesn’t do. The quantitative estimates in the report are illustrative rather than predictive. They demonstrate the kinds of insights the methodology can produce and reveal relative patterns across scenarios, but they shouldn’t be read as forecasts of actual harm levels. Much of the information needed for accurate baseline models simply isn’t publicly available. Attackers don’t publish operational statistics, and victims often have strong incentives to keep incident details private.

The models also treat defense as essentially static, which is a significant simplification. In reality, AI is transforming defensive capabilities alongside offensive ones, and the interaction between the two will shape how risks evolve. Our reliance on LLM-based estimation for most scenarios is another area requiring caution. While we validated this approach against human expert judgments for one scenario and found reasonable alignment, scaling it across all nine models introduces uncertainty we cannot fully quantify yet.

This report is a starting point. The methodology is designed to be updated as capabilities evolve, new benchmarks emerge, and better data becomes available. Extending the approach to risk domains beyond cyber offense, integrating dynamic defense modeling, and further validating LLM-assisted elicitation are all priorities for future work. We see this as a contribution toward the kind of systematic risk modeling that other safety-critical industries take for granted, and we welcome feedback from researchers and practitioners working on these problems.